Original Research

Alexandra F. Morris, PhD

Independent Scholar

Abstract

Cerebral palsy not only existed in the ancient world, but it was portrayed artistically by the ancient Egyptians. This paper examines the history of cerebral palsy in ancient Egypt, and Greco-Roman medicinal understandings of the disability. It then posits that the ancient Egyptians described and portrayed their god Harpocrates as having this disability both textually and artistically. Finally, this paper concludes by examining what life was possibly like for those with this disability in the ancient world.

Cerebral palsy, besides being a medical and societally recognised disability in the present, also existed in the distant past in ancient Egypt. Prior mummified remains have been discovered which are believed to show evidence of cerebral palsy and stroke. The ancient Egyptians also seemed to have recognised and depicted cerebral palsy in their artwork, particularly in the form of the Egyptian-Greek hybrid god Harpocrates.

Historical Overview

The earliest known example of cerebral palsy in ancient Egypt was a 13th dynasty high status woman named Geheset1. Geheset was buried in an upper-class burial, featuring an elaborate sarcophagus provided for her by her husband2. Unfortunately, the tomb itself was robbed sometime in antiquity3. Geheset is believed to have been about 5 feet tall and 50 years of age or older when she died4. An analysis of her skeletal remains led to the cerebral palsy diagnosis by the bioarchaeology team of Sandra Losch, Stefanie Panzer, and Andreas G. Nerlich. Geheset’s teeth and tempo-mandible joint were worn unevenly, with wear on the left side being significantly more pronounced than the other, and her left hand showed signs of hyperextension and flexion of the musculature5. Kyle Lewis Jordan examined her in depth in a recent presentation, and concluded that she occupied her societal positions, and was seen as a valuable societal member, in part because of the disability6.

The physician Hippocrates also described cerebral palsy in the 5th century BCE, noting the relationship between premature birth, and congenital infection or prenatal stress, with the onset of brain damage, and other disability7. He describes women who had difficult births as well as a condition which caused muscular distortions seen in infants/young children, “women who gave birth to lame, blind or children with any other deficit [disability], had foetal distress during the 8th month of pregnancy…” and “If the flow be slight, and make its descent either into both veins or into one or the other, the child recovers but bears the marks of the disease – a distortion of mouth, eye, hand or neck, according to the part from which the minor vein, filled with phlegm, was mastered and reduced.”8 More recently there has been another possible discovery by the archaeological team of Jesús Herrerín, Miguel A. Sánchez, and Salima Ikram, of someone who had hemiparalysis, a 25th dynasty woman who is believed to have been between 25-40 years old at the time of death.9 Interestingly, she was buried with walking aids which she would have needed for mobility purposes. The walking aid seems to be part of a long-standing tradition of those with disability being buried with the grave goods needed to manage those disabilities in the ancient Egyptian afterlife10.

The Case for Harpocrates

Harpocrates was a Greco-Egyptian god recognised as the son of Isis, heir of Osiris, and son of the Ptolemaic god, Serapis, and was considered to be a child iteration of Horus, the sun god11. He was considered to be the god of secrets, confidentiality, silence, the embodiment of hope, and representative of the newborn sun12. Later on, he was also recognised as a protector of mothers and children13. Harpocrates was also closely associated with the solar cult of Ptah-Sokaris, and the mortuary cult14. His fertility aspect was most closely associated with the cult of Serapis15. He also has a feminine form known as Harpocratis16. As Harpocrates was a later Greco-Egyptian iteration of Horus, artistically depictions of him did not rise in popularity until later periods in Egyptian history namely the Late and Ptolemaic Periods. Interestingly he is described by the ancient historian Plutarch as, “prematurely delivered and weak/lame in his lower limbs.”17

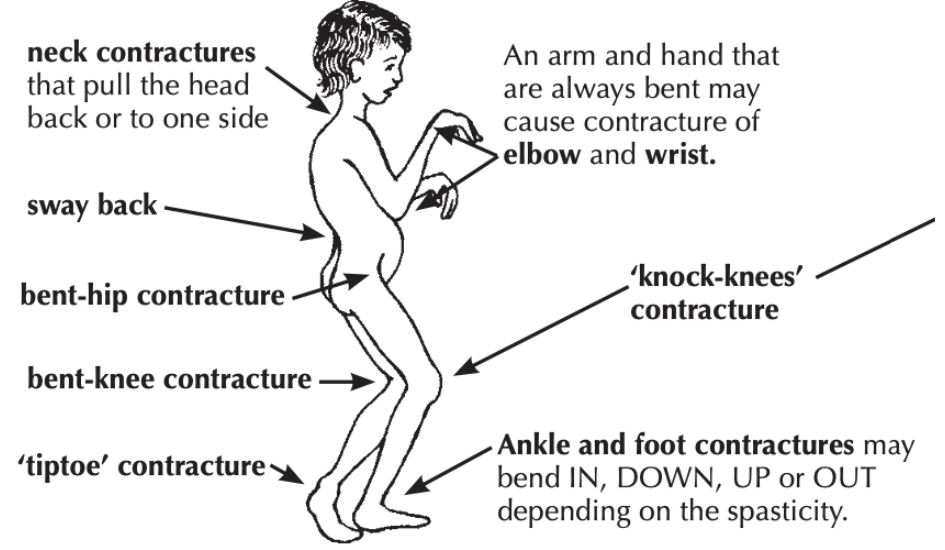

When one examines artwork of this particular god, signs of physical disability do appear to be present. These artworks include Greek or Egyptian style statues or amulets in which Harpocrates is standing, statues in which he is either in a sitting or half crawling position, statues in which he is sitting or riding on the back of animal, depictions of him breastfeeding from the goddess Isis, and depictions of Harpocratis. Art from this Ptolemaic Greco-Egyptian period was representative of a blending of different cultural styles resulting in Egyptian, Greek, and Asian-looking art. These amulets and sculptures are often made out of copper, bronze, terracotta, or glass, and some were mould made, showing that these were popular items in the ancient world18. Since there are so many depictions of this god available, due to copyright restrictions, I have included only those poses that I think are most representative in this article and are in the public domain. Some of these statues are described in their respective catalogue entries as being bent or sitting, but a closer examination reveals that they actually seem to be depicted with the crouch gait or “knock-kneed” stance commonly seen in cerebral palsy (Figure 2).19

Figure 1. Crouch Gait as Seen in Cerebral Palsy.

Physiopedia. “Cerebral Palsy: Chapter 9.” Accessed December 2022, page 101, https://www.physio-pedia.com/images/5/57/Cpt._9_Cerebral_palsy.pdf. Article and Images in the Public Domain.

Figure 2. Harpocrates. Late-Ptolemaic Period, 664-30 BCE, Faience.

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. 44.4.29.

Photos by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

It also does not make sense to describe some of them as sitting, when the angle for this is incorrect, and there is no evidence for there being a separate seat. We also have other examples where Harpocrates is clearly sitting (Figures 3-4), where the seat he is sitting on survives.20

Figure 3. Seated Harpocrates. Ptolemaic Period, 304-30 BCE, Gilded Silver.

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. 07.228.23

Photo by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Figure 4. Seated Harpocrates. Late-Ptolemaic Period, 664-30 BCE, Bronze. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. 25.184.19.

Photos by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Furthermore, when one looks at the positioning of the left hand and arm which held at the side of the torso, the palm of the hand faces downwards, and is not flat and pointing outwards towards the viewer as is seen on the examples when Harpocrates is clearly shown sitting. This positioning would not be possible if he were in fact sitting on something. This same knock-kneed stance is further replicated when Harpocrates is represented in different media such as glass amulet from the later Roman Period (Figure 5)21. Furthermore in Figure 5, one of Harpocrates’s legs is turned inwards as well, another postural trait commonly seen in those with cerebral palsy as referenced in Figure 1.

Figure 5. Amulet of the God Harpocrates. Roman Period. 30 BCE-395 CE. Glass.

Art Institute of Chicago. 1894.840. Photo by the Art Institute of Chicago.

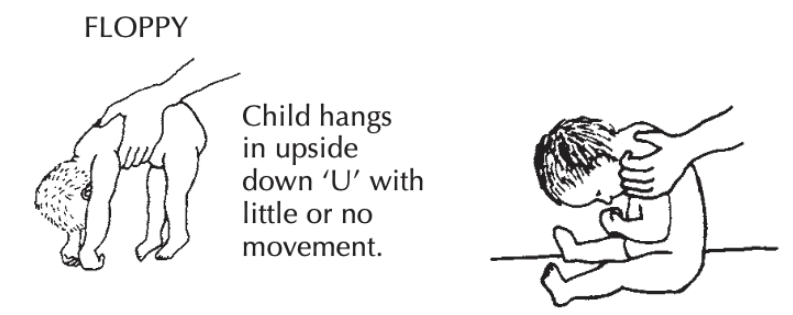

These are not the only artworks we have where signs of physical disability seem to be present. Harpocrates is also depicted as an infant in some art, usually either nursing from Isis or being carried by Isis. In these, while depicted both nude and with clothing and despite the art style being more Greek or Egyptian looking, he also seems to be depicted as a disabled infant with cerebral palsy, as the traits remain22. Harpocrates’s knees are bent inwards touching each other, with his lower legs and feet flared outwards in a knock-kneed stance, that is commonly seen in infants and young children with cerebral palsy23. Furthermore his overall posture and musculature in these statues looks floppy, and is overall an s-shape, with him seemingly not being able to hold his head up, something also commonly seen in young children with certain types of cerebral palsy.24

Figure 6. A Floppy Posture as Seen in an Infant with Cerebral Palsy. Physiopedia. “Cerebral Palsy: Chapter 9.” Accessed December 2022, page 101, https://www.physio-pedia.com/images/5/57/Cpt._9_Cerebral_palsy.pdf. Article and Images in the Public Domain.

Harpocrates also seems to be disinterested in breastfeeding, in comparison to other sculptures of Egyptian women breastfeeding infants, both divine and mortal (Figures 7-8)25. In these comparison figures, the child or deity is actively engaged in breastfeeding unlike in the representations of Harpocrates. In Figure 9, unlike the Isis in the same statue who is depicted as straight, Harpocrates seemingly leans to his left side, with his left arm also depicted as crooked and bent unlike his right arm, and his left hand seemingly depicted as turned inwards and slightly twisted. This postural weakness, overall floppy appearance, and seeming disinterest in breastfeeding is repeated in Figures 10-12. One side being weaker than the other, and posture abnormalities are other common cerebral palsy traits.

Figure 7. Group of Two Women and a Child. Middle-Early New Kingdom. 1981-1500 BCE. Limestone. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. 22.2.35.

Photo by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Figure 8. Amulet of Mut with Khonsu. Third Intermediate-Late Period. 1070-332 BCE. Faience. Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago. 1892.52.

Photo by the Art Institute of Chicago.

Figure 9. Isis Nursing Harpocrates. Ptolemaic Period, 332–30 BCE, Faience. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. 55.121.5.

Photos by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Figure 10. Isis Nursing Harpocrates. Late-Ptolemaic Period. 664-30 BCE, Faience. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. 26.7.867.

Photos by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Figure 11. Amulet of the Goddess Isis Nursing the God Horus. Third Intermediate Period. 747-656 BCE. Hematite. Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago. 1892.27.

Photo by the Art Institute of Chicago.

Figure 12. Isis Nursing Harpocrates. Late-Ptolemaic Period. 711-30 BCE. Bronze. Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. M.80.203.153.

Photo by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

In depictions of Harpocratis, the female form of this god, these posture abnormalities, and one-sided muscle weakness present in the legs, also appear to be present despite the change in gender, clothing styles, and the difference in art styles.26

Conclusions

Based on artistic and textual evidence, the Ptolemaic god Harpocrates, as well as his feminine form Harpocratis seem to have been depicted and recognised by the ancients as having cerebral palsy. As demonstrated through prior historical evidence, both the Egyptians and Greeks seem to have had knowledge of those living with this disability prior to the Ptolemaic Period as well. There also seems to have been the associated societal care of those with disabilities as, from the examples we have, they lived into adulthood and were buried with grave goods needed to help manage their conditions. The example of Geheset also demonstrates a disabled person actively involved in society and in a caretaker role in ancient Egypt. Harpocrates and Harpocratis are also demonstrative of disability being incorporated into the Egyptian and Greek religion, and must make us question the idea of there being a normative body. Disability in the ancient world needs to be examined more closely, as both medicine and society can learn from prior knowledge of the ancient world. It has always existed, and those with this condition, lived and thrived in the ancient world, and will continue to live and thrive in the present.

References

- Sandra Losch, Stefanie Panzer, and Andreas G. Nerlich. “Cerebral Paralysis in an Ancient Egyptian Female Mummy from a 13th Dynasty Tomb- Paleopathological and Radiological Investigations,” In Rupert Breitwieser, editor, Behinderungen und Beeintrachtigungen, (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2012), 37-40.

- Ibid., 37-40.

- Ibid., 37-40.

- Ibid., 37-40.

- Ibid., 37-40.

- Kyle Lewis Jordan. “Disability in Ancient Egypt: The Case of Geheset,” Unlimited Access Symposium, Allaird Pierson Museum, June 25, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fMBMdbpE-qM&t=12s

- Christos Panteliadis, Panos Panteliadis, and Frank Vassilyadi. “Hallmarks in the History of Cerebral Palsy:

From Antiquity to the mid-20th Century,” Brain & Development 35 (2013): 286: Christos Panteliadis, Christian Hagal, Deiter Karch, and Karl Heinemann. “Cerebral Palsy: A Lifelong Challenge Asks for Early Intervention,” Open Neurology Journal 9 (2015): 45-52. - Christos Panteliadis, Panos Panteliadis, and Frank Vassilyadi. “Hallmarks in the History of Cerebral Palsy:

From Antiquity to the mid-20th Century,” Brain & Development 35 (2013): 286 - Jesús Herrerín, Miguel A. Sánchez, and Salima Ikram. “A Possible Stroke Victim from Pharaonic Egypt,” World Neurosurgery (2022): E1-E4.

- Ibid: Alexandra F. Morris. “Let that Be Your Last Battlefield: Tutankhamun and Disability,” Athens Journal of History 6.1 (2020): 55-56.

- Plutarch. Loeb Classical Library: Moralia. Translated by Frank Cole Babbitt. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1936), 145-149.

- Laszio Torok. Hellenistic and Roman Terracottas from Egypt. (Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 1995), 19-21

- Ibid., 19-21.

- Ibid., 19-21.

- Ibid., 19-21.

- Ibid., 19-21.

- Plutarch. Loeb Classical Library: Moralia. Translated by Frank Cole Babbitt. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1936), 154.

- Glass Pendant in the Shape of Harpokrates (17.194.421), Hellenistic Period, 1st Century BC-1st half of 1st Century AD, Moulded Glass, H: 2.8 cm, W: 0.7 cm, D: 0.9 cm, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed February 2020, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/249658; Figure (EA60975), Late-Ptolemaic Period, 6th Century-1st Century BC, Copper Alloy, H: 8.10 cm, W: 2.30 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020,

https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx; Standing Statuette of Harpocrates in the Greek Style, Ptolemaic Period, 305-30 BC, Bronze, H: 14.8 cm, New York, Brooklyn Museum. Accessed February 2020, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/60259; Figure (1982,0301.1), Ptolemaic Period, 2nd Century-1st Century BC, Terracotta, H: 16.50 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020,

https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx - Figure; Amulet (AN1896-1908-EA.616), Late-Ptolemaic Period, 6th Century-2nd Century BC, Copper Alloy,

H: 3.70 cm, W: 0.90 cm, D: 0.50 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020,

https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx; Figure (EA49137), Late-

Ptolemaic Period, 664-31 BC, Copper Alloy, H: 2.95 cm, W: 0.80 cm, D: 0.85 cm, London, British

Museum. Accessed February 2020,

https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx; Amulet; Figure

(9,9,86,105.b), Late-Ptolemaic Period, 6th Century-1st Century BC, Copper Alloy, H: 6.80 cm, T: 2 cm,

W: 2 cm, , London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020,

https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx; Amulet; Figure (H1029.3),

Late-Ptolemaic Period, 4th Century-1st Century BC, Copper Alloy, L: 5.30 cm, T: 1.40 cm, W: 1.70 cm,

London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020,

https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx; Amulet; Figure (H1029.2),

Late-Ptolemaic Period, 4th Century-1st Century BC, Copper Alloy, H: 3.15 cm, W: 1.15 cm, D: 1 cm,

London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020,

https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx; Amulet; Figure

(9,9,86,105a), Late-Ptolemaic Period, 4th Century-2nd Century BC, Copper Alloy, H:5.70 cm, T: 1.20

cm, W: 1.70 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020,

https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx; Figure (EA60975), Late-

Ptolemaic Period, 6th Century-1st Century BC, Copper Alloy, H: 8.10 cm, W: 2.30 cm, London, British

Museum. Accessed February 2020,

https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx; Figure; Amulet (H1029.1)

Late-Ptolemaic Period, 6th Century-2nd Century BC, Copper Alloy, H: 2.20 cm, W: 1.15 cm, D: 1.25

cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020,

https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx; Figure (86.253) Late-

Ptolemaic Period, 6th Century-1st Century BC, Copper Alloy, H: 8.80 cm, London, British Museum.

Accessed February 2020,

https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx: Harpocrates. Late-Ptolemaic Period, 664-30 BCE, Faience. H: 5 cm, W: 1.6 cm, D: 1.4 cm, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. 44.4.29. Accessed December 2022, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/546236 - Seated Harpocrates. Ptolemaic Period, 304-30 BCE, Gilded Silver. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. 07.228.23. Photo by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Seated Harpocrates. Late-Ptolemaic Period, 664-30 BCE, Bronze. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. 25.184.19. Photos by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- Amulet of the God Harpocrates. Roman Period. 30 BCE-395 CE. Glass. H: 2.1 cm, W: 1 cm,

D: 0.3 cm, Art Institute of Chicago. 1894.840. Accessed December 2022,

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/140360/amulet-of-the-god-harpocrates-or-horus-

helios-with-cornucopia - Figure (1888,0601.107), Ptolemaic Period, 3rd Century-2nd Century BC, Terracotta, H: 15.50 cm, T: 4.40 cm,

W:7.70 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020,

https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx; Figure (1888,0601.108),

Ptolemaic Period, 3rd Century-2nd Century BC, Terracotta, H: 16.50 cm, T: 4.30 cm, W: 6.30 cm,

London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020,

https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx; Figure (EA63797), 30th

Dynasty-Ptolemaic Period, 3rd Century-2nd Century BC, Glazed Composition, H: 12.20 cm, W: 3.13

cm, D: 5.94 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020,

https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx - “Cerebral Palsy: Hope Through Research,” Office of Communication and Public Liaison: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Hope-Through-Research/Cerebral-Palsy-Hope-Through-Research#3104_6, last updated March 30, 2020

- Ibid.

- Amulet of Mut with Khonsu. Third Intermediate-Late Period. 1070-332 BCE. Faience. H: 6.1 cm, W: 1.7 cm, D: 3.4 cm. Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago. 1892.52. Accessed December 2022, https://www.artic.edu/artworks/135832/amulet-of-mut-with-khonsu: Group of Two Women and a Child. Middle-Early New Kingdom. 1981-1500 BCE. Limestone. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. 22.2.35. Photo by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Goblet (2002,0419.5), Ptolemaic Period, 200-30 BC, Pottery, H: 6.40 cm, W: 3.30 cm, London, British

Museum. Accessed February 2020,

https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx: Figure (1972,0125.4), Ptolemaic Period, 2nd Century-1st Century BC, Terracotta, H: 14.50 cm, London,

British Museum. Accessed February 2020,

https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx

Bibliography

“Cerebral Palsy: Hope Through Research,” Office of Communication and Public Liaison: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver- Education/Hope-Through-Research/Cerebral-Palsy-Hope-Through-Research#3104_6, last updated March 30, 2020

Herrerín, Jesús, Miguel A. Sánchez, and Salima Ikram. “A Possible Stroke Victim from Pharaonic Egypt,” World Neurosurgery (2022): E1-E4.

Jordan, Kyle Lewis. (2021) ‘Disability in Ancient Egypt: the Case of Geheset’, paper presented at Symposium: Onbeperkt Toegang/ Unlimited Access Symposium, 25th June, Amsterdam, Allard Pierson Museum [Online]. https://allardpierson.nl/events/symposium-onbeperkt-toegang/

Losch, Sandra, Stefanie Panzer, and Andreas G. Nerlich. “Cerebral Paralysis in an Ancient Egyptian Female Mummy from a 13th Dynasty Tomb- Paleopathological and Radiological Investigations,” 37-40. In Rupert Breitwieser, editor, Behinderungen und Beeintrachtigungen. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2012.

Morris, Alexandra F. “Let that Be Your Last Battlefield: Tutankhamun and Disability,” Athens Journal of History 6.1 (2020): 53-72.

Panteliadis, Christos, Christian Hagal, Deiter Karch, and Karl Heinemann. “Cerebral Palsy: A Lifelong Challenge Asks for Early Intervention,” Open Neurology Journal 9 (2015): 45-52.

Panteliadis, Christos, Panos Panteliadis, and Frank Vassilyadi. “Hallmarks in the History of Cerebral Palsy: From Antiquity to the mid-20th Century,” Brain & Development 35 (2013): 285-292.

Physiopedia. “Cerebral Palsy: Chapter 9.” Accessed December 2022, page 101, https://www.physio-pedia.com/images/5/57/Cpt._9_Cerebral_palsy.pdf. Article and Images in the Public Domain.

Plutarch. Loeb Classical Library: Moralia. Translated by Frank Cole Babbitt. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1936. Torok, Laszio. Hellenistic and Roman Terracottas from Egypt. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 1995.

Object Bibliography

Amulet; Figure (H1029.2), Late-Ptolemaic Period, 4th Century-1st Century BC, Copper Alloy, H: 3.15 cm, W: 1.15 cm, D: 1 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020, https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx

Amulet; Figure (H1029.3), Late-Ptolemaic Period, 4th Century-1st Century BC, Copper Alloy, L: 5.30 cm, T: 1.40 cm, W: 1.70 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020, https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx

Amulet; Figure (9,9,86,105a), Late-Ptolemaic Period, 4th Century-2nd Century BC, Copper Alloy, H:5.70 cm, T: 1.20 cm, W: 1.70 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020, https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx

Amulet; Figure (9,9,86,105.b), Late-Ptolemaic Period, 6th Century-1st Century BC, Copper Alloy, H: 6.80 cm, T: 2 cm, W: 2 cm, , London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020, https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx

Amulet of the God Harpocrates. Roman Period. 30 BCE-395 CE. Glass. H: 2.1 cm, W: 1 cm, D: 0.3 cm, Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago. 1894.840. Accessed December 2022, https://www.artic.edu/artworks/140360/amulet-of-the-god-harpocrates-or-horus-helios-with-cornucopia

Amulet of the Goddess Isis Nursing the God Horus. Third Intermediate. 747-656 BCE. Hematite. H: 4 cm, W: 1.6 cm, D: 2.5 cm, Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago. 1892.27. Accessed December 2022, https://www.artic.edu/artworks/596/amulet-of-the- goddess-isis-nursing-the-god-horus

Amulet of Mut with Khonsu. Third Intermediate-Late Period. 1070-332 BCE. Faience. H: 6.1 cm, W: 1.7 cm, D: 3.4 cm. Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago. 1892.52. Accessed December 2022, https://www.artic.edu/artworks/135832/amulet-of-mut-with-khonsu

Figure; Amulet (AN1896-1908-EA.616), Late-Ptolemaic Period, 6th Century-2nd Century BC, Copper Alloy, H: 3.70 cm, W: 0.90 cm, D: 0.50 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020, https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx

Figure (EA49137), Late-Ptolemaic Period, 664-31 BC, Copper Alloy, H: 2.95 cm, W: 0.80 cm, D: 0.85 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020, https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx

Figure (EA60975), Late-Ptolemaic Period, 6th Century-1st Century BC, Copper Alloy, H: 8.10 cm, W: 2.30 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020, https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx

Figure (EA63797), 30th Dynasty-Ptolemaic Period, 3rd Century-2nd Century BC, Glazed Composition, H: 12.20 cm, W: 3.13 cm, D: 5.94 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020, https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx

Figure; Amulet (H1029.1) Late-Ptolemaic Period, 6th Century-2nd Century BC, Copper Alloy, H: 2.20 cm, W: 1.15 cm, D: 1.25 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020, https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx

Figure (86.253) Late-Ptolemaic Period, 6th Century-1st Century BC, Copper Alloy, H: 8.80 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020, https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx

Figure (1888,0601.107), Ptolemaic Period, 3rd Century-2nd Century BC, Terracotta, H: 15.50 cm, T: 4.40 cm, W:7.70 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020, https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx

Figure (1888,0601.108), Ptolemaic Period, 3rd Century-2nd Century BC, Terracotta, H: 16.50 cm, T: 4.30 cm, W: 6.30 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020, https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx

Figure (1972,0125.4), Ptolemaic Period, 2nd Century-1st Century BC, Terracotta, H: 14.50 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020, https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx

Figure (1982,0301.1), Ptolemaic Period, 2nd Century-1st Century BC, Terracotta, H: 16.50 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020, https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx

Glass Pendant in the Shape of Harpokrates (17.194.421), Hellenistic Period, 1st Century BC- 1st half of 1st Century AD, Moulded Glass, H: 2.8 cm, W: 0.7 cm, D: 0.9 cm, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed February 2020, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/249658

Goblet (2002,0419.5), Ptolemaic Period, 200-30 BC, Pottery, H: 6.40 cm, W: 3.30 cm, London, British Museum. Accessed February 2020, https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx

Group of Two Women and a Child. Middle-Early New Kingdom. 1981-1500 BCE. Limestone. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. 22.2.35. Accessed December 2022, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544225

Harpocrates. Late-Ptolemaic Period, 664-30 BCE, Faience. H: 5 cm, W: 1.6 cm, D: 1.4 cm, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. 44.4.29. Accessed December 2022, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/546236

Isis Wearing a Barque Headress Suckling Her Son Horus. Late-Ptolemaic Period. 711-30 BCE. Bronze. H: 12.2 cm, W: 3.9 cm, Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. M.80.203.153. Accessed December 2022, https://collections.lacma.org/node/245529

Seated Harpocrates with the crown of Amun, named as “Harpokrates-the-great, the eldest, the first of Amun.” Late-Ptolemaic Period, 664-30 BCE, Bronze. H: 28.6 cm, W: 5.8 cm, D: 9 cm New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. 25.184.19. Accessed December 2022, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/552049

Statuette of Harpocrates. Ptolemaic Period, 304-30 BCE, Gilded Silver. H: 13.3 cm, W: 3cm, D: 7 cm, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. 07.228.23, Accessed December 2022, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/548223

Standing Statuette of Harpocrates in the Greek Style, Ptolemaic Period, 305-30 BC, Bronze, H: 14.8 cm, New York, Brooklyn Museum. Accessed February 2020, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/60259

Statuette of Harpocrates as a Child, Ptolemaic Period, 305-30 BC, Bronze, H: 14.5 cm, W: 4.5 cm, D: 8.4 cm, New York, Brooklyn Museum. Accessed February 2020, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/117176

The Goddess Isis and her Son Horus. Ptolemaic Period, 332–30 BCE, Faience. H. 17 cm, W: 5.1 cm, D: 7.7 cm, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. 55.121.5. Accessed December 2022. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/548310

Morris – Cerebral Palsy in Ancient Egypt